Don't be scared of diffusion NMR!

A friend messaged me the other day for some advice on how to run diffusion NMR measurements - or perhaps more accurately, on how not to run them. Here are some thoughts on the matter and on potential problems to be aware of when running diffusion NMR measurements. I assume basic familiarity with NMR and diffusion, and don’t meant to be at all comprehesive. If you’re starting to think about diffusion NMR but have no experience with it, I’d recommend starting with Bruker’s Diffusion NMR manual (a practical how-to guide) and then taking a look at Bill Price’s two articles on the fundamentals of pulsed gradient diffusion measurements: Part 1: Basic Theory and Part 2: Experimental Aspects.

Finally, I’ve written this post assuming that the goal is to obtain an accurate, quantitative measure of diffusion under known conditions. This is not always necessary, and it’s probably OK to be less careful when using diffusion measurements for more qualitative tasks (e.g. resolving the components of a crude mixture by DOSY NMR).

Diffusion: basic physics

What governs diffusion rates? The Stokes-Einstein-Sutherland equation for the diffusion of a hard spherical particle at low Reynolds number tells us:

\[D = \frac{k_B T}{6\pi\eta R_H}\]where \(k_B\) is Boltzmann’s constant, \(T\) is the (absolute) temperature, \(\eta\) is the dynamic viscosity, and \(R_H\) is the hydrodynamic radius of the diffusing particle - the radius of a hard-edged sphere that would diffuse at the same rate. Real molecules are generally neither spherical nor hard-edged, so be careful when relating \(R_H\) to actual dimensions. I think of the hydrodynamic radius as an effective measure of the average size of a molecule incorporating any supramolecular ordering that may form: \(R_H\) of a single chemical species might vary in different solvents as a result of supramolecular (self-)association through solvent coordination, H bonding, ion pairing, cation-\(\pi\) interactions, and so on. As an example, Li+ ions coordinated in THF might appear “bigger” than Li+ in non-coordinating hexane. \(R_H\) can also vary based on the population distributions of different conformers or tautomers that may be favoured in different solvent environments.

It might be tempting to argue that \(\eta\) is fixed for a given solvent and that temperature changes will be relatively small for a system at 298 K +/- a degree or so, and that diffusion is thus only really sensitive to \(R_H\) changing. This is not the case: for most solvents the viscosity \(\eta\) also varies strongly as a function of temperature, making the overall diffusion measurement much more sensitive to changes in temperature. Empirical measurements have found that the dependence of diffusion on temperature is often closer to an exponential Arrhenian relationship:

\[D(T) = A\exp{(-\frac{E_a}{k_B T})}\]It’s not at all clear to me if \(A\) and \(E_a\) are physically meaningful quantities. This Arrhenian relationship also tends to break down for more “structured” solvents with stronger intermolecular interactions, such as water and small alcohols. Here are some reported values of the “activation energy” for diffusion of common molecular solvents:

| Solvent | \(E_a~\mathrm{/~kJ~mol^{-1}}\) |

|---|---|

| Cyclohexane | 13.7 |

| Dioxane | 13.9 |

| Dodecane | 13.7 |

| DMSO | 14.9 |

| Tetradecane | 15.6 |

| Pentanol | 24.1 |

The take-home here is that diffusion measurements are specific to a solution temperature, and that good temperature control and/or monitoring (try a methanol capillary!) are essential for quantitative diffusion measurements.

Diffusion NMR

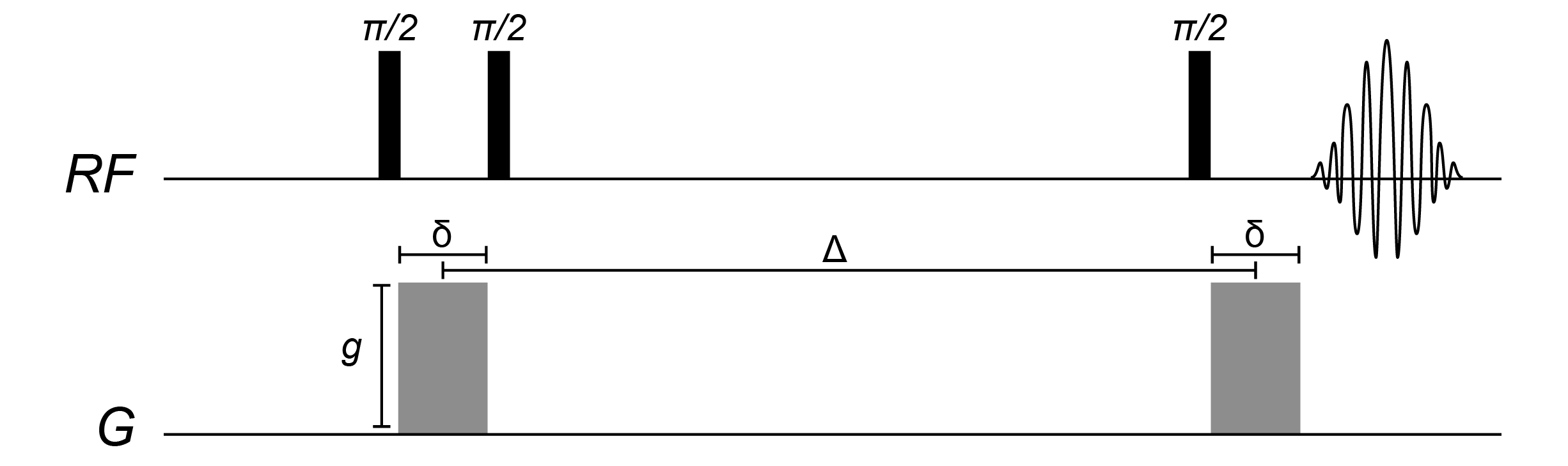

Pulsed-gradient diffusion NMR measurements involve:

- Acquiring a sequence of 1D spectra with a range of gradient pulse strengths

- Extracting the intensities (integrals or peak heights) of peaks of interest

- Fitting the Stejsal-Tanner equation to these intensities as a function of gradient strength, and obtaining diffusion coefficients

The Stejskal-Tanner equation relates the acquired signal intensity \(I\) to the gradient pulse amplitude \(g\), nuclear gyromagnetic ratio \(\gamma\), gradient pulse length \(\delta\) and measurement time \(\Delta\), and diffusion coefficient \(D\). The exact form of this equation varies for different pulse sequences and gradient pulse shapes, but a typical formulation (assuming perfectly square gradient pulses) is:

\[I = I_0 e^{-D(g^2\delta^2\gamma^2(\Delta-\delta/3))}\]In theory we can run a diffusion experiment by varying any one of \(g\), \(\delta\), or \(\Delta\). In practice, \(\delta\) and \(\Delta\) are almost always held constant while the gradient pulse amplitude \(g\) is varied across a set range of typically 0–50 gauss/cm.

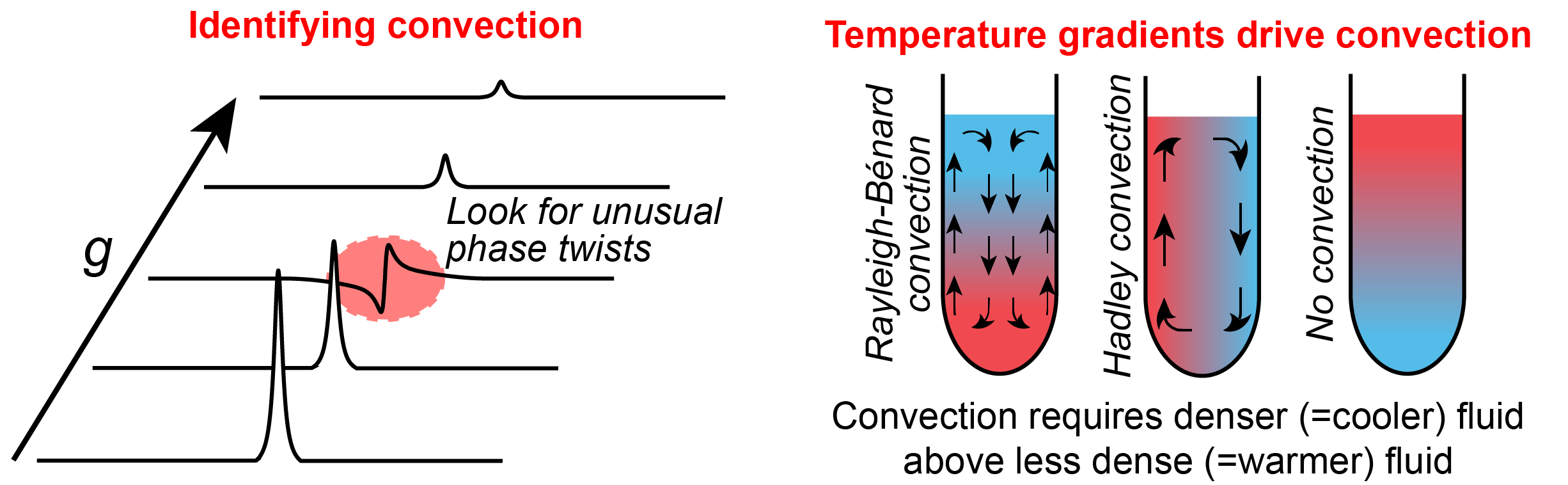

Convection

Convection is probably the most persistent problem affecting diffusion NMR measurements. It results from small temperature gradients across the sample, can occur at any time, and should never be forgotten or ignored. Convection is more likely in some systems than others: an experiment run with a room temperature-equilibrated instrument on a small sample in viscous DMSO is unlikely to suffer from convection, while a punching in a 20° temperature increase on a CDCl3 sample and running a diffusion experiment the moment the target temperature is reached will almost guarantee convection. Time-resolved diffusion measurements of dynamic reacting systems or systems under irradiation are also likely to suffer from convection.

Here are some signs of convection to look for when running diffusion NMR experiments:

- Convection will often cause phasing artefacts (see above), making it impossible to correctly phase all slices of the diffusion experiment at the same time. Always look at the spectral data before using it.

- Convection is somewhat random. Repeat the same measurement several times: if the results vary meaningfully, this may indicate convection.

- Convection will always result in an obtained diffusion coefficient higher than the real diffusion coefficient. If a range of diffusion coefficients are measured for the same sample, the lower values are likely to be more accurate than the higher values.

- The convection-induced error in a measurement increases roughly proportionally to \(\Delta\), the diffusion measureing time, while diffusion measurements are independent of \(\Delta\). Run a series of experiments with different \(\Delta\): if \(D\) increases with \(\Delta\), this is likely convection. The true diffusion coefficient can sometimes be found by fitting a line through multiple \(D(\Delta)\) measurements and extrapolating to \(\Delta = 0\).

Here are some tips for avoiding or preventing convection:

- Use a more viscous solvent. Experiments in DMSO-d6 are much less likely to suffer from convection than experiments in CDCl3; experiments at low temperature (=increased viscosity) are less likely to suffer from convection than experiments at high temperature (=decreased viscosity).

- Give the instrument plenty of time to equilibrate after temperature changes, and avoid changing the temperature unnecessarily.

- Use non-standard smaller NMR sample tubes: convection is less likely to occur in more narrow geometries. I’ve had success in replacing standard 5 mm NMR tubes with smaller 3 mm tunes. Similarly, don’t overfill your sample: 0.5 mL in a standard tube is plenty.

- Pack the sample with a physical obstruction to impede flow. I’ve had success (see SI) by adding short pieces of broken glass TLC capillaries to a standard sample tube, and I’ve heard good things about glass wool. Avoid magnetic or high surface area materials - you want to disrupt flow without changing the chemical or magnetic environment. This approach can make shimming take a little longer, but I’ve found that lineshapes are normally OK eventually.

For more on this topic, see this paper and many others from Gareth Morris’ research group: Sample convection in liquid-state NMR: Why it is always with us, and what we can do about it.

Final note: some diffusion NMR pulse sequences incorporate “convection suppression” elements, designed to filter out and remove the influence of convection. I don’t really understand how this works and am skeptical of relying on convection-suppressing sequences to filter out the effects of convection, rather than using the approaches above to physically prevent it.

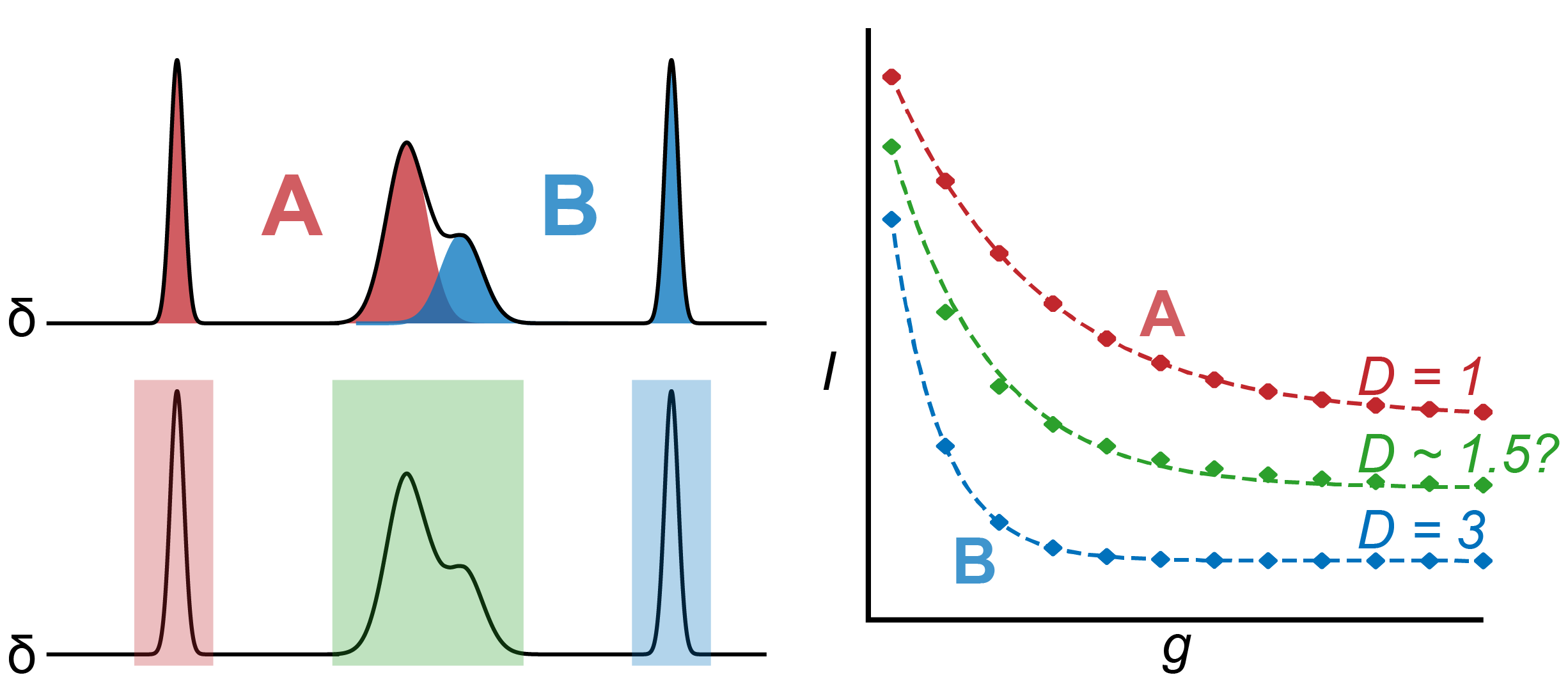

Overlapping peaks give averaged diffusion coefficients

Diffusion coefficients are obtained by fitting NMR peak intensities to the Stejskal-Tanner equation. “Intensity” here normally refers to either the peak integral or the peak amplitude: I prefer to use integrals due to the higher signal-to-noise and insensitivity to small changes in lineshape or shim during the experiment. But what happens when integrating a region of the spectrum captures overlapping peaks from multiple chemical species, or when looking at a peak corresponding to multiple chemical species in fast exchange? The data will give an averaged diffusion coefficient sitting somewhere between the diffusion coefficients of the overlapping species.

If the overlapping species have reasonably different diffusion coefficients, it’s sometimes possible to separately resolve their diffusion coefficients by fitting a multiexponential function to the obtained data—something like:

\[I = I_1 e^{-D_1(g^2\delta^2\gamma^2(\Delta-\delta/3))}_1 + I_2 e^{-D_2(g^2\delta^2\gamma^2(\Delta-\delta/3))}\]Unfortunately, resolving overlapping peaks into separate diffusion coefficients like this tends to be difficult and uncertainties on the fitted parameters are often large. In most cases it’s probably better to throw away the overlapping peaks and limit your analysis to the well-resolved peaks of interest.