Enhanced Diffusion

Do chemically active catalysts diffuse more quickly than they should do?

Introduction

The central focus of my PhD was controlling the translational motion of molecules in solution. After deciding that mechanically articulated molecular swimming was unlikely to be experimentally measurable, my interest turned to intriguing reports of “enhanced diffusion” of chemically active enzymes and small molecular catalysts as measured by FCS, DLS, microfluidics experiments, and pulsed-gradient diffusion NMR. As a chemist and NMR spectroscopist I was happy to leave the optical studies of enzymes to others, and so chose to look at the diffusive behaviour of molecular catalysts as-measured by NMR spectroscopy. We also wanted an excuse to work with diffusion NMR specialist Bill Price at Western Sydney University!

The question of enhanced diffusion eventually became a major focus of my PhD, leading to several nice papers and contributions to (one side of) an ongoing scientific controvery.

Diffusion NMR of transient processes

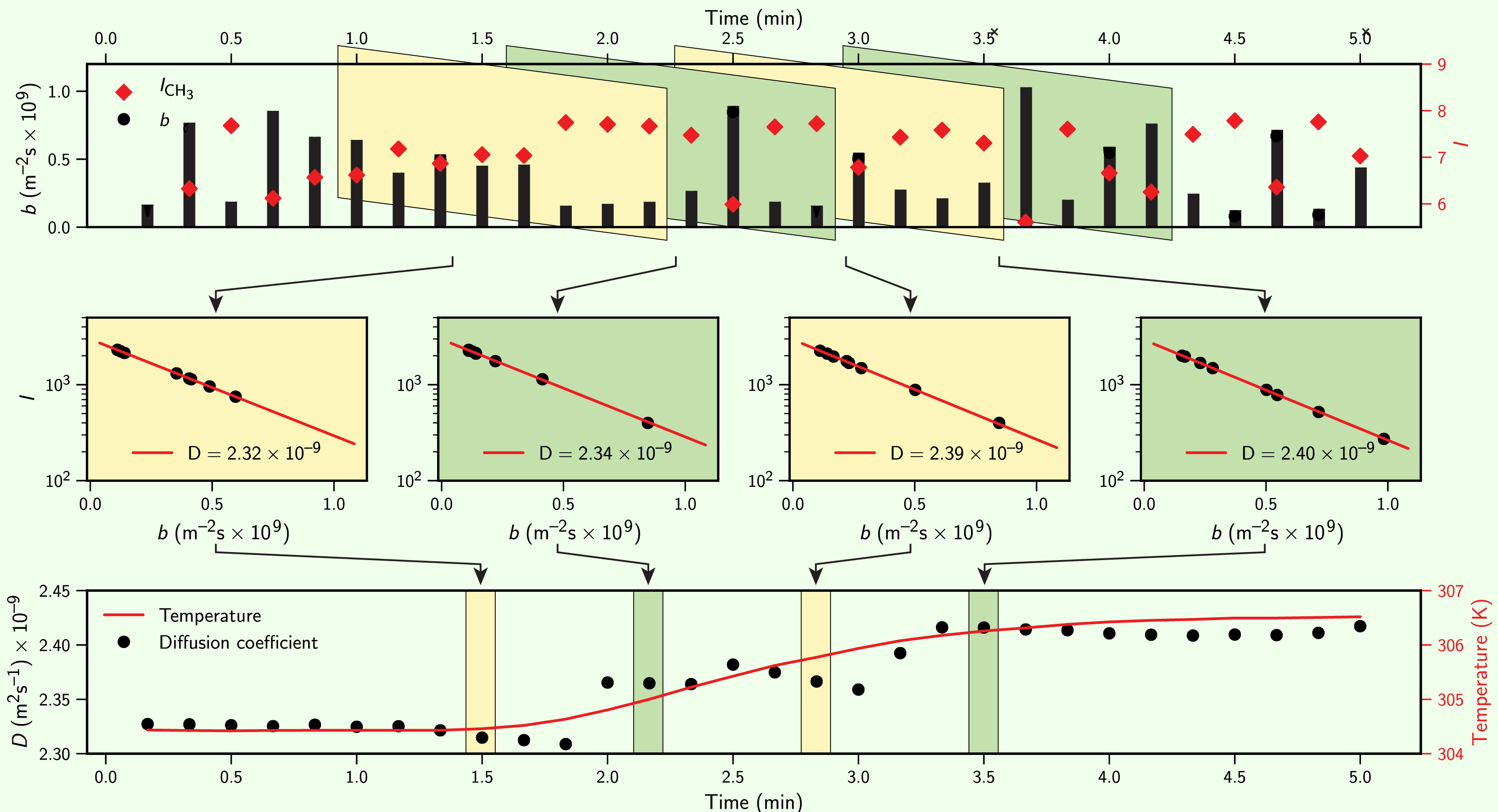

1D NMR spectroscopy is often used to follow time-dependent systems like chemical reactions, but time-dependent NMR studies of diffusion are much less common. Standard diffusion NMR experiments assume a static system and take perhaps 20-30 minutes to acquire a single diffusion measurement (16 gradients, 16 scans per gradient, >5 s per scan), which is quite slow compared to many reaction timescales. Measuring small, transient changes in diffusion under these standard conditions seemed unsatisfying, so I set out to develop a better approach to time-resolved diffusion NMR measurements. We ended up settling on a simple but effective approach of continuously acquiring spectra while drawing from a long sequence of pseudo-random gradient pulses, shown below. This approach let us acquire diffusion measurements as fast as we could could acquire single-point spectra, typically 0.5-3 minutes for 4-16 point phase cycles.

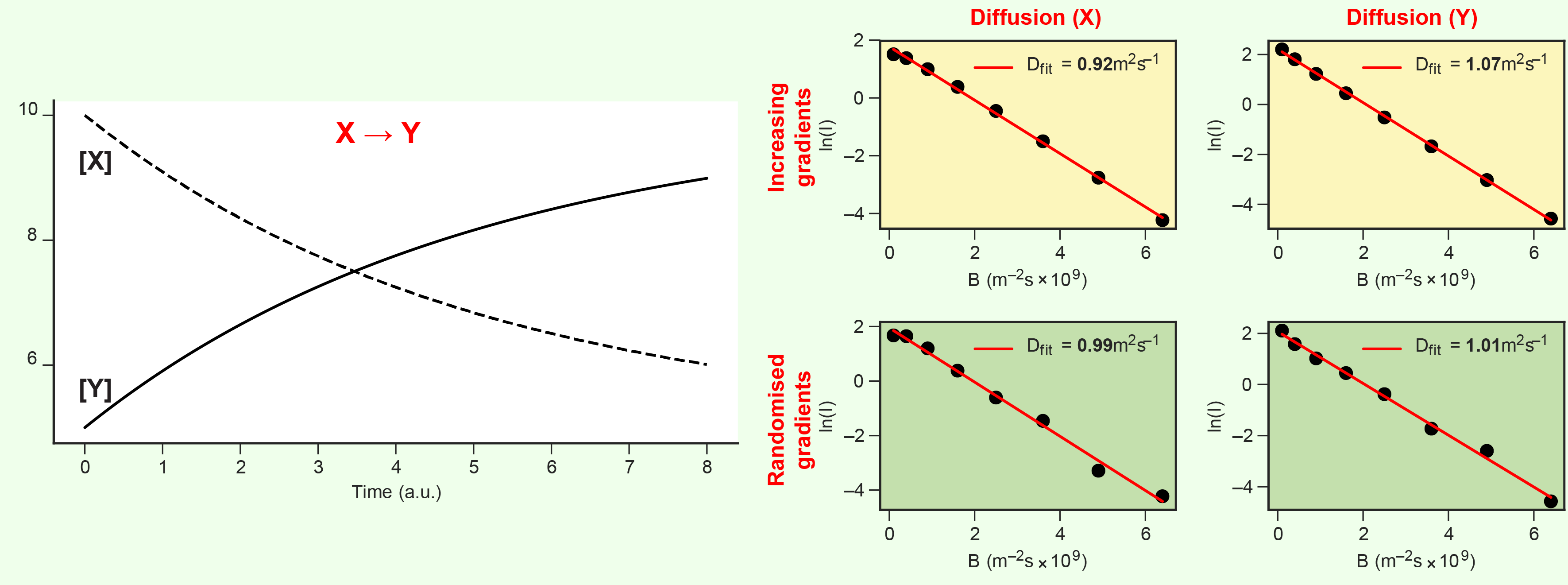

I realised fairly quickly during this project that random gradient sequences (as above) aren’t only useful for seamless continuous data acquistion. Because diffusion NMR experiments measure signal intensities resulting from a sequence of gradients applied over time, experiments using correlated gradient sequences (e.g. monotonically increasing or decreasing) are vulnerable to artefacts when the measured signal intensity increases or decreases for other reasons during the experiment. A monotonically increasing gradient sequence, for example, will overestimate the measured diffusion coefficient of a chemical species with decreasing concentration during the experiment. Randomising the sequence of gradients used in a diffusion experiment to eliminate any monotonic correlation is a simple, low-effort measure to remove these artefacts.

At the time, I thought this problem of cross-correlated gradient sequences and signal intensities was interesting but unlikely to be significant in practice. In the example above, concentrations doubling or halving during a complete gradient sequence only caused a ~10\% error in diffusion measurements: a relatively small error from what seemed an unrealistically fast reaction process. What I didn’t recognise at the time but would help identify later was that signal intensities can sometimes change much more rapidly than reaction kinetics in an NMR experiment, such as when relatively small changes in the concentration of paramagnetic species result in large changes of system-wide relaxation rates.

Having developed a way to rapidly acquire NMR diffusion measurements of evolving systems, it was finally time to take a closer look at the mysteries of enhanced diffusion.

Diffusion NMR and convection

A re-examination of reported enhanced diffusion of molecular catalysts.

Derek Lowe wrote a blog post on this project and its outcomes, ticking off an item from my chemistry bucket list - I’ve been reading his blog since I was maybe 13 or 14 years old, so having my work featured on it was quite a moment.

Diffusion NMR and changing signal intensities

This topic really kicked off in 2020 following the publication of a paper in Science claiming observations of enhanced diffusion for a copper-catalysed “click” reaction, as measured by diffusion NMR and microfluidics. With limited evidence of experimental protocols given and no raw data provided at the time, it was hard to evaluate this critically. The NMR measurements at least seemed to show a number of flaws: the gradient lists used were monotonic (vulnerable to artefacts when correlated against changes in signal intensity, as above), diffusion enhancements were presented only in relative \(\Delta D/D_0\) terms normalised against an unknown “\(D_0\)” with no absolute measured values given, and some of the language used seemed to suggest only a passing familiarity with diffusion NMR. I was able to contribute to a joint critique of these claims as a postscript to my then-submitted PhD, which triggered a response to the critique followed by an avalanche of comments and full papers over the next six months. First the original authors reiterated their claims (JPCL), prompting another comment critiquing those claims and a reply to the comment, then another reiteration of enhanced diffusion (ACS nano) opposed by a near-simultaneous third rebuttal as a joint paper (JACS) from three research groups collectively finding no evidence of enhanced diffusion but demonstrating the potential of changing concentrations of paramagnetic relaxants (like Cu(II)) to interfere with NMR diffusion measurements.

The saga will probably continue from here. My opinion is that the original observation of “enhanced diffusion” likely resulted from a combination of factors:

- Steady-state changes in real \(D\) during the reaction led to an apparently ‘enhanced’ relative \(\Delta D/D_0\) when divided by the unusually small end-of-reaction \(D_0\).

- The confusion of diffusion coefficients from multiple species with overlapping chemical shifts, leading to time-dependent changes in ‘average’ \(D\) as the composition of the overlapping signals changed during the reaction

- Artefacts from a semi-monotonic gradient sequence correlated with rapidly changing signal intensities from paramagnetic-induced relaxation from the Cu(I)-Cu(II) redox couple.

Enhanced diffusion: real or illusion?

What to make of all this? I think the most important conclusion is that while diffusion NMR is a powerful spectroscopic technique, it’s also vulnerable to a range of measurement artefacts. These can be caused by non-diffusive translational motion (convection, molecular chemotaxis), correlations between the gradient sequence and changing signal intensities, and errors in processing and data presentation (such as relative changes in diffusion ‘normalised’ against arbitrary parameters). Diffusion NMR remains far from a ‘black box’ experimental technique, and NMR measurements of diffusion still require critical analysis grounded in an understanding of NMR fundamentals. Some of these artefacts can be (and should be!) eliminated through improvements in experimental protocals, such as replacing all monotonic gradient sequences with non-correlated shuffled sequences, while others still require specialist knowledge to identify, diagnose, and remove.

As for the enhanced diffusion of molecular catalysts, I remain skeptical. I have not encountered a convincing physical model that suggests it should be possible, and experimental reports of enhanced catalyst diffusion have struggled to be replicated or withstand scrutiny. The experimental evidence for enhanced enzyme diffusion seems somewhat better, but the predominantly-FCS diffusion studies have their own potential issues involving the disassociation of enzyme into smaller subunits at low concentrations. This field also suffers from an ongoing confusion of controversial and mysterious “enhanced diffusion” with entirely non-controversial chemical chemotaxis up or down a concentration gradient. Several reports have used microfluidics experiments to demonstrate the motion of active catalysts up or down a concentration gradient of substrate: while this is interesting in its own right and potentially a useful way to drive transport at the nano-scale, it is explicitly not “enhanced diffusion” above what would be expected normally.

For those interested in reading some more scholarly thoughts on enhanced molecular diffusion by a team that haven’t been in the trenches themselves (so to speak), Yifei Zhang and Henry Hess wrote a good critical review on this contentious topic in May 2021.